OPINION: This article may contain commentary which reflects the author's opinion.

The U.S. Supreme Court heard two cases last week that could mark the end of what observers have described as a four-decade “constitutional revolution” that began during the Reagan administration.

Specifically, decisions in the cases could substantially change how federal agencies are permitted to interpret laws passed by Congress by dramatically reigning in their ability to issue rules that have the binding effect of legislation.

According to Thomas M. Boyd, a former US assistant attorney general who served under President Ronald Reagan, Justice John Paul Stephens wrote an opinion in the case of Chevron U.S.A. v. National Resources Defense Council in 1984, midway through Reagan’s two terms, which started what legal scholar Gary Lawson would later describe as “nothing less than a bloodless constitutional revolution.”

The ruling fundamentally changed the way federal agencies could interpret laws they considered to be “ambiguous.” Following this decision, subsequent presidential administrations utilized it to enforce policies that effectively functioned as laws, often deviating from the exact wording of the legislation passed by Congress.

But now, Boyd noted in a column for the New York Post, “At long last, on Wednesday, the Supreme Court will hear two cases that may signal the beginning of the end to that revolution.”

Boyd noted that Article I of the Constitution says explicitly, “All legislative power herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States”—not federal regulatory agencies.

However, he adds, Justice Stephens’ opinion found that “agenc[ies] may . . . properly rely upon the incumbent administration’s views of wise policy” in “reasonably” defining statutory ambiguities.

In simpler terms, Stephens believed that the Executive Branch, including presidents and their appointees, had the power to determine the specific interpretations of certain aspects of laws enacted by the Legislative Branch.

That, Boyd noted, was at the center of the Chevron decision and became known as the “Chevron defense, leading President Ronald Reagan’s White House counsel, Peter Wallison, to describe it as ‘the single most important reason the administrative state has continued to grow out of control.'”

Boyd writes: “Forty years of regulatory and judicial tumult have ensued, finally crescendoing to a point that has compelled the Supreme Court to intervene.

Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, from the District of Columbia Circuit, and Relentless v. Department of Commerce, from the First Circuit, are now before the court. Both are companies that fish for herring in New England and are family-owned and operated, and both are subject to the Magnuson-Stevens Act, which governs fishery management in federal waters. The act allowed the National Marine Fisheries Service to require herring boats, relatively small vessels that normally carry only five to six people, to also carry federal monitors to enforce its regulations.”

It gets worse.

The former Reagan assistant attorney general mentioned that the agency, without explicit statutory authorization, proceeded to require Loper Bright and Relentless to bear the expenses for the salaries of these monitors. The NMFS estimated these costs at $710 per day, at times exceeding the income generated from a day’s fishing.

Both federal circuit courts ruled that statutory silence on the matter was an “ambiguity” that required the application of the Chevron deference.

But when the Supreme Court accepted certiorari in both cases, justices proposed a two-part question that litigants would be required to address: “Whether the Court should overrule Chevron or at least clarify that statutory silence concerning controversial powers expressly but narrowly granted elsewhere in the statute does not constitute an ambiguity requiring deference to the agency.”

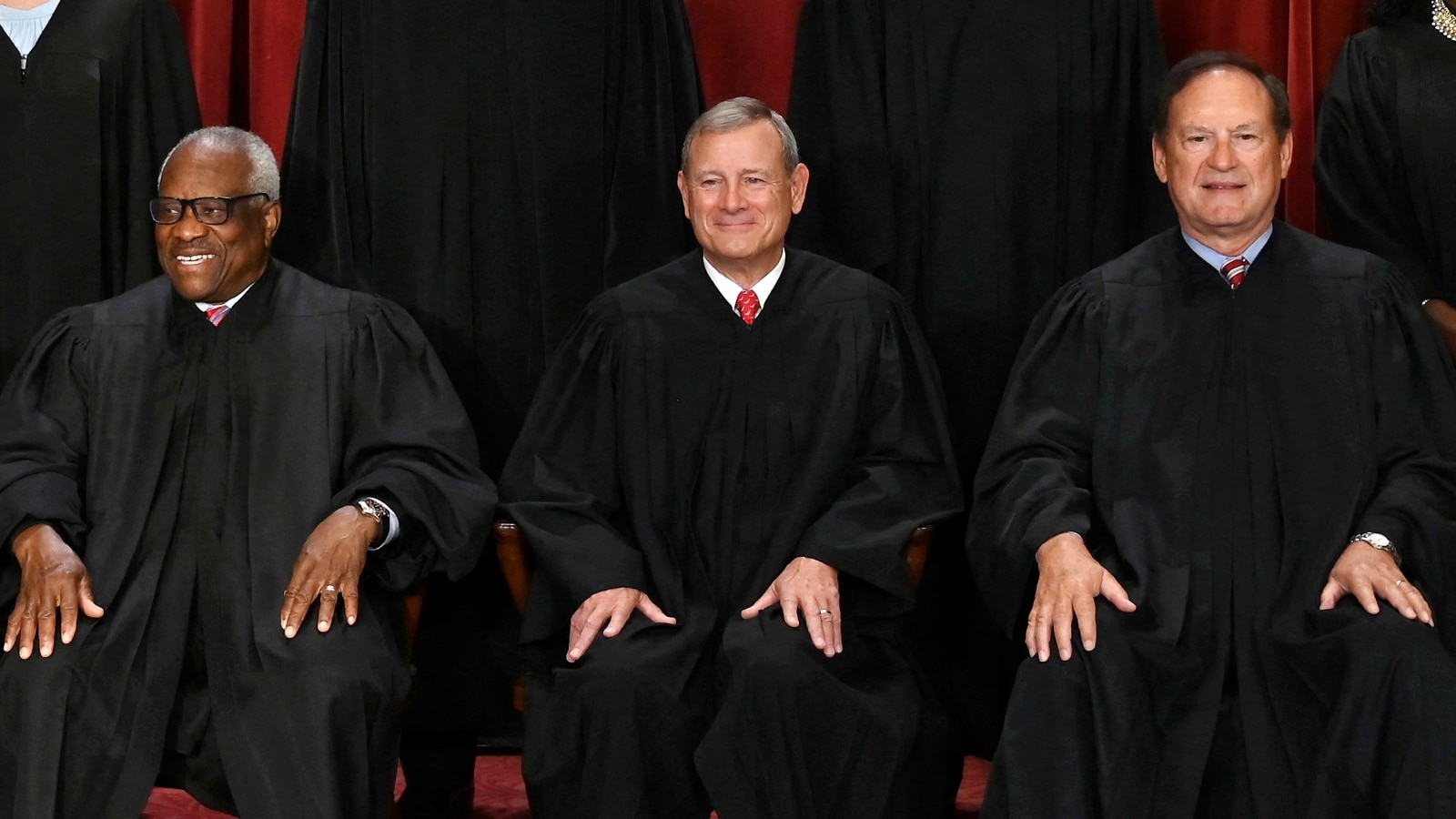

Boyd noted that some of the court’s current justices—constitutional originalists, in fact—have indicated in previous opinions how they view the matter.

Several have indicated suspicion in allowing federal agencies — and, by definition, the Executive Branch in general — too much leeway in the interpretation of laws, giving them nearly limitless power in governing, Boyd noted.